Article by PBI-Colombia

The story of the “Who gave the order” mural was wrought with censure from the start. The image was covered with white paint just hours after it was painted on 18 October 2019, in front of the General José María Córdova Military Academy in Bogotá. According to statements from the Movement of Victims of State Crimes – MOVICE [1]—the organization that promoted the initiative—the mural was censured in an operation by the 13th Brigade of the National Army when over 20 armed men intimidated the young artists who painted the mural. [2] A day later, MOVICE published on Twitter that the mural had been censured. Despite numerous attempts to halt its dissemination, the symbol of memory for victims of extrajudicial executions and the call for truth, justice, and guarantees of non-repetition is once again in front of the Military Academy and is now protected by the Colombian Constitutional Court.

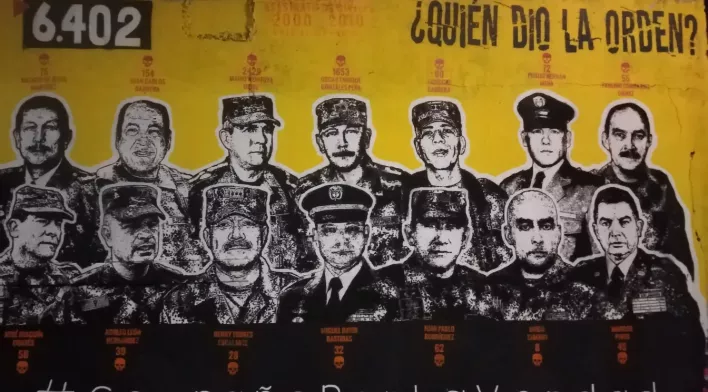

The image was designed in 2019 by the Campaign for Truth [3]—a coalition of several human rights organizations—and portrays the faces of five high-level military commanders, under the command of whom 5,763 extrajudicial executions were perpetrated during the 2000 to 2010 period. [4] These are the cases of the so-called “false positives,” a euphemism that refers to the murder of youth who are presented as guerrillas killed in combat. This is one of the darkest chapters of the Colombian armed conflict and a central element to be addressed by the transitional justice system.

At the end of 2019, one of the commanders who appears on the mural, General Marcos Evangelista Pinto Lizarazo, commander of the 13th Brigade, filed a tutela (writ of protection of constitutional rights) to have the mural erased from social media given that, according to him, MOVICE actions damaged his honor and good name. This legal action [5] was joined by the Commander of the National Army of Colombia between 2006 and 2008, General Mario Montoya Uribe [6] who also appears on the mural. In February 2020, Civil Court 13 of Bogotá ruled in favor of the military high commanders’ request, arguing that while there are no judicial rulings against the military leadership, the victims could not express their opinion. [7] Hence, the court ordered that the mural be pulled within 48 hours from the streets and social media. [8] However, it was impossible to comply: the image of the mural had already been shared hundreds of times by digital users and around 5,000 posters with the mural image had flooded the streets of Bogotá[9] and, later, other Colombian cities. MOVICE accepted the judicial ruling that censured the important call to clarify “who gave the order” while, as the investigations advanced, the increasing magnitude of extrajudicial executions in Colombia was corroborated.

On 12 July 2018, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) decided to open case 003: “Illegitimate deaths presented as individuals killed in combat by state agents.” As a part of the process to establish the extent of extrajudicial executions as a phenomenon, the JEP studied a vast amount of information. Even though sources differ on the magnitude of the crime investigated by the JEP, they all indicate that the largest number of victims was during the 2002 to 2008 period. Investigations show that during this period, a historic 78% of the total victimizing events were registered. The methodology for Case 003 is “from the bottom upwards,” and seeks to investigate the phenomenon first on a local level to later move to the regional and national levels. Regarding the responsible parties, the mural promoted by the “Campaign for Truth” indicates that “who gave the order” must be clarified, in other words, an identification of the high-level commanders of the Colombian Army who ordered the crimes.

After carrying out a verification process among different commissions and entities, [10] the Chamber to Acknowledge Truth of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, which arose out of the Peace Agreement, declared that “throughout the national territory at least 6,402 individuals were illegally killed and presented as killed in combat between 2002 and 2008.” The numbers revealed in the Special Jurisdiction for Peace report also confirm the hypothesis presented by the organizations on the existence of a military policy that favored the persistence of this crime, which was perpetrated without any control, verification, or punishment for the responsible parties. The policy combined methods from the dirty war with personal and institutional incentives and benefits that lacked transparency and sought to give the appearance of military success and security. [11]

After almost two years of legal actions to resolve the issue of the legitimacy of this emblem of memory for victims and their fight for truth, the Constitutional Court ruled, [13] on 9 November 2021, to protect freedom of expression and the victims’ memory. The Court argued that the mural “Who gave the order” must be protected due to the gravity of the incidents that surround extrajudicial executions, the immense impact on Colombian society, and the responsibility of army members who are currently being investigated for their alleged participation in incidents, which the petitioners have presented as systematic actions. In turn, the Court declared that “Who gave the order” is a critique of the state, which is clearly part of the public debate, given that government employees could be involved in serious human rights violations. Hence, the Court noted that the victims have the right to an extrajudicial truth as it “contributes to the construction of historical memory. The public narrative that these provide, in addition to being an inclusion mechanism, also restore the victims’ right to honor and allows them to materialize the guarantee to tell their own truth. Therefore, it can be stated that attempted censorship can result in a revictimization of those affected by these crimes.” [14]

Thanks to the work of social organizations, human rights organizations, and victims this jurisprudence in favor of freedom of expression made it possible for artists and human rights organizations to repaint the mural in front of the Military Academy on 4 December. This time it reflected the shocking 6,402 victims of extrajudicial executions and 14 high-level commanders who are allegedly responsible. The mural “Who gave the order” has in itself a very important meaning as it was possible due to a ruling that favors freedom of expression and, at the same time, is a strong vindication of justice and truth. Until Colombia can answer the question “who gave the order?” the families of the victims of extrajudicial executions will continue the search for truth and justice in a brave and necessary exercise of active memory.

“Society needs to know what happened. This is also a part of the victims’ and society’s right to speak out against impunity on the serious crimes that have hurt them and to demand a full truth so that this is never repeated.” [15]

PBI Colombia.

[1] MOVICE: Con tutela buscan censurar mural ¿Quién dio la orden?, 30 October 2019.

[2] CAJAR: SOS Contra la Censura, October 2019.

[3] The iniciative is from the #CampañaPorLaVerdad (Campaign for Truth), which unites several human rights organizations that have historically represented victims of state crimes, such as MOVICE, CAJAR, CSPP, CJL, and JyP. It is an iniciative to make state crimes visible in the context of transitional justice.

[4] This number comes from a report published in 2014 by the Working Group on Extrajudicial Executions of the Coordination Colombia Europe United States and the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR): “The Rise and Fall of ‘False Positive’ Killings in Colombia: The role of US Military Assistance, p. 69 and 126. Research titled “Extrajudicial Executions in Colombia, 2002-2010. Blind obedience in fictitious battlefields” was also published and refers to 10,000 extrajudicial executions, just during the 2002-2010 period.

[5] MOVICE: Juez declara improcedentes tutelas en contra del Movice por mural ¿Quién dio la orden?, 14 November 2019.

[6] The most emblematic case is that of General Mario Montoya Uribe, Commander of the Army between 2006 and 2008, who the Prosecutor’s Office has accused of being responsible for the murder of 104 individuals—five of whom were minors presented as combat casualities. At the end of August 2021, the Superior Tribunal of Bogotá, denied the Prosecutor Office’s request that the case of Mario Montoya—accused of aggravated homicide and concealment and tampering of evidence in “false positives” cases—be charged by the ordinary justice system. Hence, , his case will remain at the JEP.

[7] MOVICE: Mural ‘¿Quién dio la orden?’ ya es patrimonio de la sociedad: Movice, 25 February 2020.

[8] El Confidencial: ¿Quién dio la orden? Un asunto de interés público, 21 November 2021.

[9] El Espectador: Intimidaciones y allanamientos: así se hizo el mural “¿Quién dio la orden?”, 21 November 2021.

[10] The Prosecutor General’s Office, the Inspector General’s Office, the Accusatory Penal System, the Observatory on Memory and Conflict of the National Center for Historical Memory, the Coordination Colombia Europe United States.

[11] CAJAR: JEP reconoce la magnitud de los “falsos positivos.” Son más de 6.000 casos, las víctimas tenían razón, 18 February 2021.

[12] Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz: Asesinatos y desapariciones forzadas presentados como bajas en combate por agentes del Estado.

[13] Corte Constitucional: Sentencia T-281/21, 23 August 2021.

[14] El Confidencial: ¿Quién dio la orden? Un asunto de interés público, 21 November 2021.

[15] José Alvear Restrepo Lawyers’ Collective – CAJAR.