On March 22, World Water Day, PBI Guatemala traveled to the southern coast and visited several communities that are part of the Retalhuleu Community Council (CCR), an organization PBI has accompanied for five years. The goal of this trip was to learn firsthand about the problems these communities face with regard to water. The communities are organized and are fighting for their right to water. We witnessed harrowing and outrageous realities and heard detailed testimonies that cry out for the urgent implementation of measures to alleviate the suffering of these families and communities.

While hundreds of people participated in the protest for the right to water in Mazatenango that day, in the 20 de Octubre neighborhood, ten minutes from Champerico, residents gathered with their children and grandchildren to playfully raise awareness about the importance of water, which is essential for the life of all species. Their slogans were “Without water there is no life” and “Water is life, not a commodity.”

CCR member Reselda Mejía told us that her struggle is not for her generation, but rather for future generations, saying, “We want our children to know about our struggle and participate in defense of our rights, because this is a struggle that will not end with me. It must continue… to defend the rivers, nature, and our hard-working people who have been silenced.” That is why they explain to children that “they have rights: to health, education, food, play, recreation, and a healthy environment.” These are rights that are being denied to them, as we saw during our visit to five communities in the region, accompanied by Reselda. Community representatives spoke to us about their living conditions, particularly how the lack of access to water is affecting them.

“If I don’t work, I don’t eat”

In the 20 de Octubre neighborhood, we met Adán de León. This 70-year-old resident had just climbed out of a well he was digging on the other side of the road and came over to say hello, as we had met him on previous visits. We asked him if he wasn’t too old to dig wells, to which he replied that he had to do something to live, as he had no help whatsoever and, despite his advanced age, no income, saying, “If I don’t work, I don’t eat.” He says that poverty in the neighborhood is rampant, there are no jobs, young people and parents have migrated, and children suffer from malnutrition. There is no land left to farm, and planting corn on rented land is not profitable because the cost of renting land and buying seeds and fertilizers is so high that it cannot be offset by the income from the crop. In addition, the lack of rain, the scarcity of other water sources, and unpredictable weather events are extra risks on top of those already mentioned.

Adán came to the community 30 years ago because there was water. There were rivers and marshes that provided food every day. But with the arrival of the sugar cane companies, deforestation began. “When I saw them cutting down tree after tree, I said that it would be a disaster for Champerico, and that’s what happened. That’s how it is now.” Then “they sprayed pesticides into the air, and it fell on the marshes, killing the shrimp and fish. There is no more fishing. The pollution is extremely serious. It affects children’s health, but they don’t care. We struggle, but we can’t get rid of the sugar cane.”

Adán explains that water no longer reaches the 20 de Octubre neighborhood, and that it hardly ever rains anymore. Fortunately, for the past six years, “we have had a water tank for the neighborhood and drinkable water in our homes, but they didn’t build any drainage, so dirty water pools in the streets and causes a lot of pollution. Now a butcher shop opened on the street where the drain is located. Imagine, the flies come, drink the water and then land on the meat.” We have gone to every state authority and every new administration and “presented the problem to them, but we have not received a response.” However, Adán has not lost hope that one day they will find a project that will finance the installation of a drainage system for their neighborhood, “otherwise we will all end up sick.” “We have to keep fighting for future generations, because our children and grandchildren will not be able to live here if there is no water or if all the water is polluted.”

“We want the river to flow normally”

A neighbor who arrived from the hamlet of Carrizales, in the municipality of La Blanca, San Marcos, where 85 people currently live. “We are not yet part of the CCR, but we want to be, because water is a big problem for us. The rivers no longer flow where they used to because they are blocked or dammed. Motorized pumps are used to divert the river to other places to irrigate palm and banana plantations. That is why we suffer with the river.” He is a fisherman and farmer, and both professions are being affected by the water shortage caused by agro-industries. The diversion of the rivers leaves them with “rust-colored, stagnant water that no longer flows freely and where there are no longer any fish.” Agricultural production has become difficult because “we lease land to plant, but seeds are very expensive, as is fertilizer. We live off corn; we no longer have other crops because the plantations fumigate from airplanes, polluting the air and water. That’s why we no longer plant tomatoes, chili peppers, watermelons, or cucumbers. Furthermore, the water wells have dried up. So it’s not worth it anymore. The rich have been getting in the way of us farmers for a long time.” What you see in the community are “children with health problems due to water pollution, crops that no longer grow, and many elderly people and single mothers who have nothing to eat.”

Sugar cane companies are largely responsible for this situation, as the sugar harvest begins in November and “they start fires, which heat up the environment and dry up the water.” Their products are transported in large trucks, which ruin the roads, and “it is us, the farmers, who have to fix them.”

They have tried to engage in dialogue with the company owners, but they do not want to “talk to their representative, they want to talk to the wealthy owner” to find solutions. So far, they have been unsuccessful. “Many people allow themselves to be bought off with a bag of beans. But we don’t want gifts paid for with our taxes; we want support so that we can work our land.”

“Our fish are dying”

In the village of Barrio El Palmo in Champerico, we met a group of fishermen who lament the fact that they can no longer work in their profession due to water scarcity and pollution. Daniel Santos Ambrosio Pérez, 55, said, “We fish with nets, with the water up to our chests, our waists, our knees. And sometimes we go out to the deepest parts in canoes. Fish grow in the marshes and lagoons and then go out to sea. In the summer, we suffer because the marshes get shallower, as the rivers dry up and the sea no longer feeds them, since we are 10 meters below sea level. So we wait for the rain to come and fill the rivers, which will feed the lagoons and marshes and allow the fish to grow.”

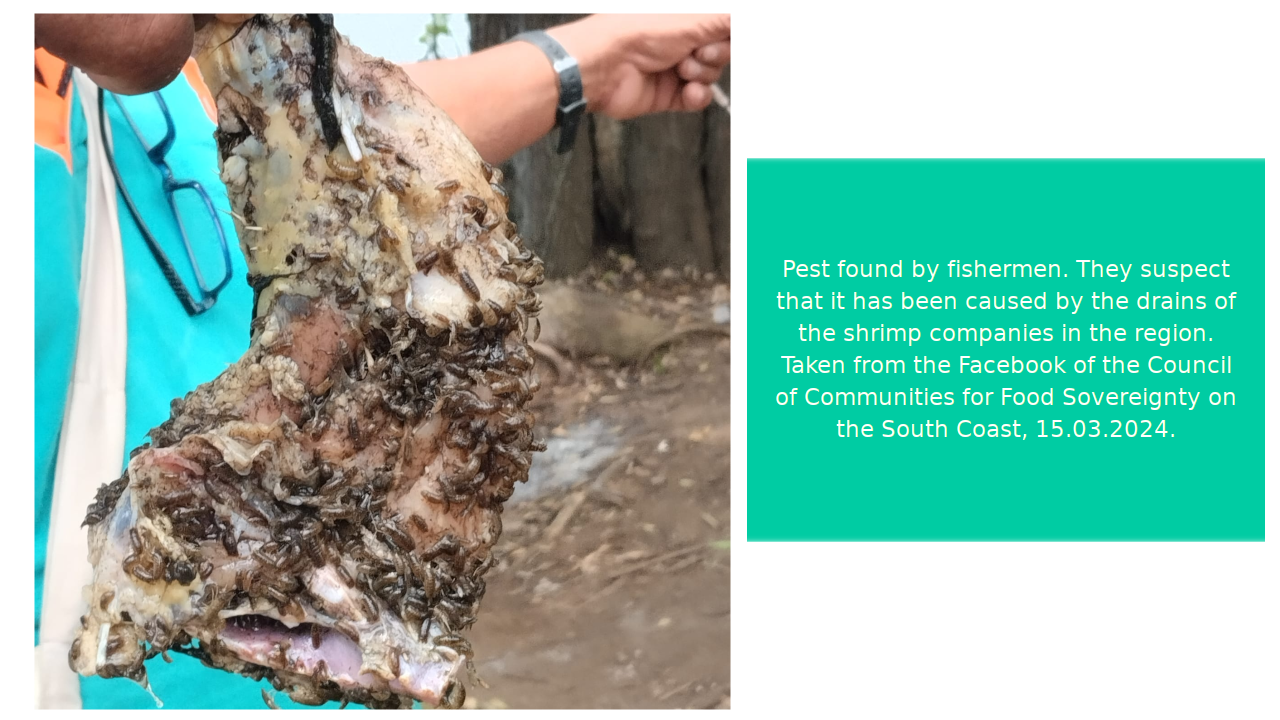

Juan Luis Baten García adds that the problems with this drought began when “the sugar cane companies arrived. They come with their motorized pumps to suck the water out of the rivers, so the rivers no longer feed the marshes.” In the summer, the marshes “are only half a meter deep and heat up in the sun, so the fish die, the larvae die because there is no moisture for them to live, and the shrimp die from the chemicals sprayed on them” when the cane growers spray their fields.

Daniel urges companies not to block the rivers, “so that the water reaches its destination and the marshes don’t dry up. We used to fish for different species such as shrimp, fish, crabs, mollusks, abalone, and clams that grow on the roots of the mangroves. But in the dry season, the water no longer flows because the plantations block it and pump it out for their crops. We need to catch the fish to sell them and use the money to buy beans and rice so that our families can survive.”

Juan Luis, 63 years old, says that when he was 18 and came to the port to fish, he would take home 100 pounds of fish to sell at the market. However, “not anymore. Now the companies are here, and they don’t let us fish. There are no other job opportunities here, only fishing.” Pollution of the marshes is another issue, because industrial fishing companies use insecticides and discharge their waste into natural lagoons and marshes, creating infestations of larvae (sea lice) that eat the fish. Juan Luis laments that the government does not monitor companies to ensure they comply with their obligations and the law, and that they do not rob the population of job opportunities and food. That is why he is not surprised that there are “many thieves and criminals in Champerico, because there are no sources of income.”

They also work the land, but “nowadays it hardly ever rains.” Daniel recalls that they used to plant “on May 10, and by August there was already corn; we planted sesame seeds, and by November there was already sesame. Now that’s no longer the case. My dad used to tell me that the dry spell began on July 12 and ended on August 12. Now July is pure dry season, and the cornfields die. We need water; we don’t want the rivers to be dammed up.”

“We are just surviving”

The water situation is the same in the community of Nueva Gomera, where a group of five women and one man were waiting for us. The community was founded about 15 years ago when several families moved here from the community of Gomera, in Escuintla, because the population had grown and there was no more land available. Victor Chocojay, the eldest member of the group, recalls, “We came here to access land, we didn’t come to invade or steal. When we arrived, there were trees and the water was nine or ten meters deep, but now it’s 18 or 20 meters away from us. When we arrived, there was water, but now the rainy seasons come very late. The most common crop is corn, but if it doesn’t rain, nothing grows. The palm and sugar cane companies are to blame. Deforestation and watering the sugar cane fields day and night take away our water, destroy our crops, and bring us disease because of environmental pollution. We are suffering greatly because of the issue of water.”

The husbands of the women who attended the meeting work in the cane fields, working shifts ranging from eight to 24 hours. Some work all year round, but the majority only work from October to May. They take advantage of the break to work their fields, but if it doesn’t rain, they can’t harvest anything. They complain that “what they earn from sugarcane isn’t enough to support their families. There was a recent pay increase of Q150 every two weeks, but they also increased the number of hours we work, and with the rise in the cost of living, we haven’t felt any benefit from the increase.” They told us that they cannot speak out about labor rights abuses. The men who work in the sugar cane company remain silent about working conditions because “if they complain, they will lose their jobs, and we will suffer even more.” They would have no chance of finding work in another company because they would be blacklisted. “That’s why our children suffer from malnutrition.”

Twelve people from the community organized themselves to start family gardens. They began the project four years ago when health authorities identified many malnourished children. This was because “the prices of vegetables and greens rose too high.” Before, they would go to the river to wash and fetch water, but now, in order to water their gardens, cook, wash, and drink, they have to ask a neighbor who has a well deep enough to draw water. In their gardens, they plant black nightshade, sweet peppers, jalapeños, tomatoes, and chipotle, among other crops. “We share what we harvest from the gardens among ourselves and save the seeds to plant more. This is how we get by, more or less.”

Don Victor remarked that there is significant migration to the United States, but due to the recent change in administration there, “now they are being sent back, so the situation will become more complicated because there are no job opportunities here. The government has abandoned us, they have forgotten about us, and all the communities are in the same situation.”

“What we are asking is that companies fulfill their social responsibility, that they be conscious, that they stop digging deeper wells and that they plant trees so that the water level does not drop any further. We are not asking for money, nor do we want anything for free. We want them to take the surrounding community into account and not exploit their workers. We just want them to fulfill their responsibility.”

“There is no rainwater anymore”

In San Juan El Húmedo, we meet Verónica Díaz Caxaj, who shows us her 12-by-12-meter garden. There, she grows different kinds of fruits and vegetables, such as star apples, bananas, plantains, chipotle, tomatoes, beans, yucca, sweet potatoes, chocolate peppers, corn, and sesame seeds, thanks to a drip irrigation system with hoses that run between the plants. Every morning, she opens a tap on a tank where the family collects water used for washing dishes and their hands, and a small motor pumps the water for an hour or more, depending on the plants’ needs. Verónica has been tending the garden for 10 years, and her family of nine lives off what they grow there. “We barter with neighbors who grow other kinds of crops.”

She says that the water shortage began around 2010. Since then, rainfall has declined, and the capacity of the wells has decreased. Last year, there was absolutely no rain in her community. There was no corn harvest. “Now we recycle water because there is no rainwater. We have declared this area the dry corridor.” She also explains that the Samalá River, which runs about 2.5 kilometers away from her land, no longer has much water because “Luis García’s plantation has taken it and diverted it to irrigate his pasture, to have his green area and so his animals can graze, taking water away from the community and also causing flooding on the road. Go and see for yourselves.”

Flooding on dry land

We drove along a local road connecting the communities of Las Victorias and San Juan El Húmedo until we came to a flooded dirt road. You have to know the area well to know where to drive to get through the flood without getting too wet. “There is little flooding right now. In the rainy season, when they coincide with heavy rains, the road becomes dangerous and, while the flooding lasts, the children of San Juan cannot go to school in Las Victorias.”

Local residents of the communities are outraged by the attitude of Spanish plantation owner Luis García, who runs a cattle and lemon farm and diverts the river for his own benefit. This prevents the river from flowing along its usual course, filling wells and emptying into the sea. It also causes flooding that harms residents of neighboring communities. This is especially painful during the dry season, when they have no access to drinking water and yet find water being wasted along the road, hindering movement between these two communities, particularly for those who travel on foot.

Local residents have brought their complaints to various political authorities, including the governor’s office, but they have been ignored. “We have already sent him a formal request to allow the river to flow freely and stop causing flooding, but he doesn’t care. He ignores our complaints. He also treats his employees however he wants, exploiting them and thinking he is better than them because he is Spanish. He has already been sued for labor rights violations, as he does not pay in accordance with the law, does not pay the minimum wage or IGSS (social security) contributions for his workers, and takes advantage of the precarious working conditions in the region. Two people sued him and won, but these two people can no longer find work on the farms here. He only looks out for his own interests; he doesn’t think about his workers or his neighbors.”

“We want to eat something healthy”

In each community, we found family gardens of different sizes. Depending on the land available, they range from 10-15 to 50-100 square meters. They grow radishes, chipotle, beets, cabbage, tomatoes, Swiss chard, black nightshade, chili peppers, and, when there is more water available, cucumbers, cantaloupe, and watermelon, as these require a lot of water to grow. Reselda explains that “four years ago, CCR began organizing family gardens in communities to ensure food security for families and combat child malnutrition. This provides us with naturally nutritious plants rich in minerals and vitamins. We also fertilize them with our own natural fertilizer made from ash, lime, and eggshells.” The women are in charge of the gardens, as they are the ones who use the most water during the day due to their household chores. “We are more aware of water usage and know how to recycle water. We have received training on how to use it. We produce crops even though the rivers and watersheds no longer provide us with enough water.” The crops are only for family consumption, as there is not enough to sell because of the water shortage caused by the hoarding of rivers by agribusinesses.

“We are organizing women and youth to speak out against all the harm and violence that is being done to us. We are women defenders, and we believe that we have power, even though we have been attacked, discriminated against, and humiliated in different ways. But we have decided to no longer remain silent, to make our voices heard, to make the Ministry of the Environment aware and get them to take action, to make the government see our needs and see what we are going through. We are not asking for crumbs or charity, we are asking for our rights to be respected and fulfilled, the rights granted to us by the Constitution. We are human beings, we have blood, we have life, we want to continue to have clean air, we want to feel the rain, we want it to fall on us. We no longer have rain because of all the logging, they are polluting our air and our rivers with so much agribusiness, sugar cane, palm oil, and bananas. The water no longer flows where it should: to the sea. We no longer see the clouds gathering over the sea to fill up with water and bring it to us. This affects our agricultural system; our crops no longer yield like they used to.

“We are tired of so much pollution. We want to eat something healthy, something we have produced ourselves. When I sit down at my table, I can eat black nightshade and know that it is healthy and free of chemicals. When I barter, I know that I am giving something good and not giving cancer or other diseases caused by Monsanto or Bayer,” the corporations that sell genetically modified seeds and fertilizers. “They come and play with our health.”

On World Water Day, “we appeal to the conscience of the industry. There is no water left in Champerico. The southern coast is asking you to leave let the rivers flow free. Water is life,” and if you threaten water, you threaten life.